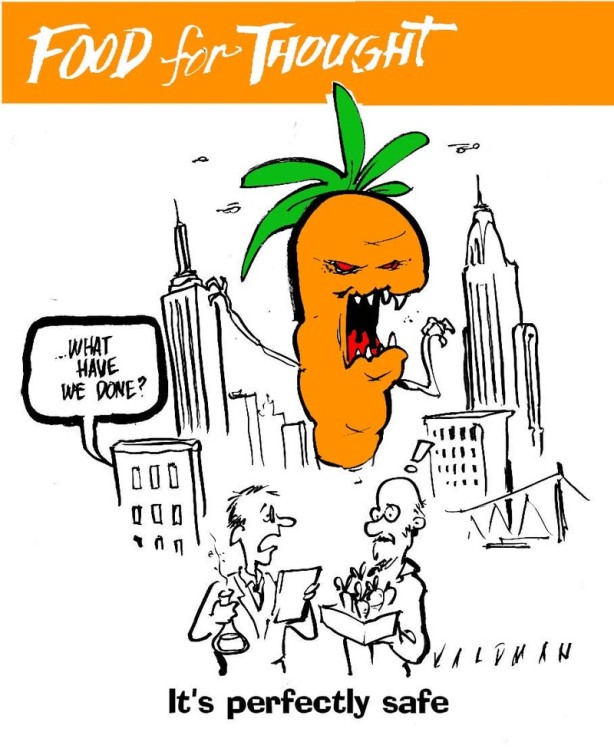

The following Guardian article talks about another one of those half-cocked geo-engineering fixes: liming the world’s oceans. The guy who promotes the idea is a former management consultant, which immediately raises the question: what makes him qualified to design climate change solutions?

Apart from that minor detail, this band aid, like all the other ones, makes no attempt to determine any possible consequences of lime dumping for the complex web of interactions within the oceanic environment as well as between it and weather patterns.

Sometimes I feel these self-proclaimed geo-engineers are the modern equivalent of snake oil peddlers …

Just add lime (to the sea) – the latest plan to cut CO2 emissions

• Project ‘could turn back clock’ on carbon dioxide

• Guardian conference will select top 10 climate ideas

Duncan Clark

The Guardian

Putting lime into the oceans could stop or even reverse the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, according to proposals unveiled at a conference on climate change solutions in Manchester today.

According to its advocates, the same technique could help fix one of the most dangerous side effects of man-made CO2 emissions: rising ocean acidity.

The project, known as Cquestrate, is the brainchild of Tim Kruger, a former management consultant. “This is an idea that can not only stop the clock on carbon dioxide, it can turn it back,” he said, although he conceded that tipping large quantities of lime into the sea would currently be illegal.

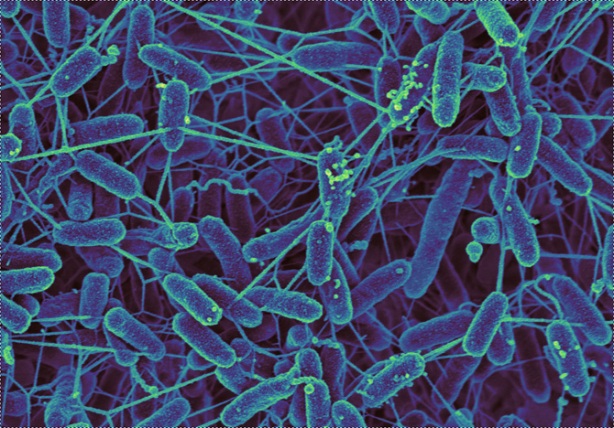

The oceans are a key part of the natural carbon cycle, in which carbon dioxide is circulated between the land, seas and atmosphere. About one-third of the CO2 released into the air by humans each year is soaked up by the oceans. This helps slow the rate of global warming but increases ocean acidity, posing a potentially disastrous threat to marine ecosystems.

Kruger’s scheme aims to boost the ability of the oceans to absorb CO2 but to do so in a way that helps reduce rather than increase ocean acidity. This is achieved by converting limestone into lime, in a process similar to those used in the cement industry, and adding the lime to seawater.

The lime reacts with CO2 dissolved in the water, converting it into bicarbonate ions, thereby decreasing the acidity of the water and enabling the oceans to absorb more CO2 from the air, so reducing global warming.

Kruger said: “It’s essential that we reduce our emissions, but that may not be enough. We need a plan B to actually reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. We need to research such concepts now – not just the science but also the legal, ethical and governance considerations.”

Kruger’s plan was one of 20 innovative schemes proposed at the Manchester Report, a two-day search for the best ideas to tackle climate change staged by the Guardian as part of the Manchester International Festival.

A panel of experts chaired by Lord Bingham, formerly Britain’s most senior judge, will select the 10 most promising ideas. These will be featured in a report that will be published in the Guardian next week and circulated to policymakers around the world.

Climate change secretary Ed Miliband told the conference the biggest danger faced by campaigners was creating a sense of defeatism. “We need to show people how they can aggregate their individual actions and be part of a bigger whole,” he said.

Cquestrate is one of a number of so-called “geo-engineering schemes” that have been proposed to intervene in the Earth’s systems in order to tackle climate change.

Kruger admits there are challenges to overcome: the world would need to mine and process about 10 cubic kilometres of limestone each year to soak up all the emissions the world produces, and the plan would only make sense if the CO2 resulting from lime production could be captured and buried at source.

Chris Goodall, one of the experts assessing the schemes, said of Cquestrate: “The basic concept looks good, though further research is needed into the feasibility.”

Another marine geo-engineering scheme was presented by Professor Stephen Salter, of Edinburgh University.

His proposal is to build a fleet of remote-controlled, energy-self-sufficient ships that would spray minuscule droplets of seawater into the air. The droplets would whiten and expand clouds, reflecting sunlight away from the Earth and into space.

Salter said 300 ships would increase cloud reflectivity enough to cancel out the temperature rise caused by man-made climate change so far, but 1,800 would be needed to offset a doubling of CO2, something expected within a few decades.

Further Reading

New Geoengineering Scheme Tackles Ocean Acidification, Too (Wired Science)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)